What Is the Definition of Competitive Exclusion Principle in Biology

Proposition that two species competing for the same limiting resource cannot coexist at constant population values

"Gause's law" redirects here. It is not to be confused with Gauss's law.

1: A smaller (yellow) species of bird forages across the whole tree.

2: A larger (red) species competes for resources.

3: Red dominates in the middle for the more abundant resources. Yellow adapts to a new niche restricted to the top and bottom and avoiding competition.

In ecology, the competitive exclusion principle,[1] sometimes referred to as Gause's law,[2] is a proposition named for Georgy Gause that two species competing for the same limited resource cannot coexist at constant population values. When one species has even the slightest advantage over another, the one with the advantage will dominate in the long term. This leads either to the extinction of the weaker competitor or to an evolutionary or behavioral shift toward a different ecological niche. The principle has been paraphrased in the maxim "complete competitors can not coexist".[1]

History [edit]

The competitive exclusion principle is classically attributed to Georgyii Gause,[3] although he actually never formulated it.[1] The principle is already present in Darwin's theory of natural selection.[2] [4]

Throughout its history, the status of the principle has oscillated between a priori ('two species coexisting must have different niches') and experimental truth ('we find that species coexisting do have different niches').[2]

Experimental basis [edit]

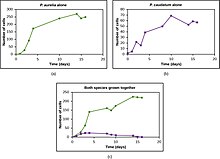

Based on field observations, Joseph Grinnell formulated the principle of competitive exclusion in 1904: "Two species of approximately the same food habits are not likely to remain long evenly balanced in numbers in the same region. One will crowd out the other".[5] Georgy Gause formulated the law of competitive exclusion based on laboratory competition experiments using two species of Paramecium, P. aurelia and P. caudatum. The conditions were to add fresh water every day and input a constant flow of food. Although P. caudatum initially dominated, P. aurelia recovered and subsequently drove P. caudatum extinct via exploitative resource competition. However, Gause was able to let the P. caudatum survive by differing the environmental parameters (food, water). Thus, Gause's law is valid only if the ecological factors are constant.

Gause also studied competition between two species of yeast, finding that Saccharomyces cerevisiae consistently outcompeted Schizosaccharomyces kefir [ clarification needed ] by producing a higher concentration of ethyl alcohol.[6]

Prediction [edit]

Competitive exclusion is predicted by mathematical and theoretical models such as the Lotka–Volterra models of competition. However, for poorly understood reasons, competitive exclusion is rarely observed in natural ecosystems, and many biological communities appear to violate Gause's law. The best-known example is the so-called "paradox of the plankton".[7] All plankton species live on a very limited number of resources, primarily solar energy and minerals dissolved in the water. According to the competitive exclusion principle, only a small number of plankton species should be able to coexist on these resources. Nevertheless, large numbers of plankton species coexist within small regions of open sea.

Some communities that appear to uphold the competitive exclusion principle are MacArthur's warblers[8] and Darwin's finches,[9] though the latter still overlap ecologically very strongly, being only affected negatively by competition under extreme conditions.[10]

Paradoxical traits [edit]

A partial solution to the paradox lies in raising the dimensionality of the system. Spatial heterogeneity, trophic interactions, multiple resource competition, competition-colonization trade-offs, and lag may prevent exclusion (ignoring stochastic extinction over longer time-frames). However, such systems tend to be analytically intractable. In addition, many can, in theory, support an unlimited number of species. A new paradox is created: Most well-known models that allow for stable coexistence allow for unlimited number of species to coexist, yet, in nature, any community contains just a handful of species.

Redefinition [edit]

Recent studies addressing some of the assumptions made for the models predicting competitive exclusion have shown these assumptions need to be reconsidered. For example, a slight modification of the assumption of how growth and body size are related leads to a different conclusion, namely that, for a given ecosystem, a certain range of species may coexist while others become outcompeted.[11] [12]

One of the primary ways niche-sharing species can coexist is the competition-colonization trade-off. In other words, species that are better competitors will be specialists, whereas species that are better colonizers are more likely to be generalists. Host-parasite models are effective ways of examining this relationship, using host transfer events. There seem to be two places where the ability to colonize differs in ecologically closely related species. In feather lice, Bush and Clayton[13] provided some verification of this by showing two closely related genera of lice are nearly equal in their ability to colonize new host pigeons once transferred. Harbison[14] continued this line of thought by investigating whether the two genera differed in their ability to transfer. This research focused primarily on determining how colonization occurs and why wing lice are better colonizers than body lice. Vertical transfer is the most common occurrence, between parent and offspring, and is much-studied and well understood. Horizontal transfer is difficult to measure, but in lice seems to occur via phoresis or the "hitchhiking" of one species on another. Harbison found that body lice are less adept at phoresis and excel competitively, whereas wing lice excel in colonization.

Phylogenetic context [edit]

An ecological community is the assembly of species which is maintained by ecological (Hutchinson, 1959;[15] Leibold, 1988[16]) and evolutionary process (Weiher and Keddy, 1995;[17] Chase et al., 2003). These two processes play an important role in shaping the existing community and will continue in the future (Tofts et al., 2000; Ackerly, 2003; Reich et al., 2003). In a local community, the potential members are filtered first by environmental factors such as temperature or availability of required resources and then secondly by its ability to co-exist with other resident species.

In an approach of understanding how two species fit together in a community or how the whole community fits together, The Origin of Species (Darwin, 1859) proposed that under homogeneous environmental condition struggle for existence is greater between closely related species than distantly related species. He also hypothesized that the functional traits may be conserved across phylogenies. Such strong phylogenetic similarities among closely related species are known as phylogenetic effects (Derrickson et al., 1988.[18])

With field study and mathematical models, ecologist have pieced together a connection between functional traits similarity between species and its effect on species co-existence. According to competitive-relatedness hypothesis (Cahil et al., 2008[19]) or phylogenetic limiting similarity hypothesis (Violle et al., 2011[20]) interspecific competition[21] is high among the species which have similar functional traits, and which compete for similar resources and habitats. Hence, it causes reduction in the number of closely related species and even distribution of it, known as phylogenetic overdispersion (Webb et al., 2002[22]). The reverse of phylogenetic overdispersion is phylogenetic clustering in which case species with conserved functional traits are expected to co-occur due to environmental filtering (Weiher et al.,1 995; Webb, 2000). In the study performed by Webb et al., 2000, they showed that a small-plots of Borneo forest contained closely related trees together. This suggests that closely related species share features that are favored by the specific environmental factors that differ among plots causing phylogenetic clustering.

For both phylogenetic patterns (phylogenetic overdispersion and phylogenetic clustering), the baseline assumption is that phylogenetically related species are also ecologically similar (H. Burns et al, 2011[23]). There are no significant number of experiments answering to what degree the closely related species are also similar in niche. Due to that, both phylogenetic patterns are not easy to interpret. It's been shown that phylogenetic overdispersion may also result from convergence of distantly related species (Cavender-Bares et al. 2004;[24] Kraft et al. 2007[25]). In their study, they have shown that traits are convergent rather than conserved. While, in another study, it's been shown that phylogenetic clustering may also be due to historical or bio-geographical factors which prevents species from leaving their ancestral ranges. So, more phylogenetic experiments are required for understanding the strength of species interaction in community assembly.

Application to humans [edit]

Evidence showing that the competitive exclusion principle operates in human groups has been reviewed and integrated into regality theory to explain warlike and peaceful societies.[26] For example, hunter-gatherer groups surrounded by other hunter-gatherer groups in the same ecological niche will fight, at least occasionally, while hunter-gatherer groups surrounded by groups with a different means of subsistence can coexist peacefully.[26]

See also [edit]

- Limiting factor

- Limiting similarity

- Paradox of the plankton

References [edit]

- ^ a b c Garrett Hardin (1960). "The competitive exclusion principle" (PDF). Science. 131 (3409): 1292–1297. Bibcode:1960Sci...131.1292H. doi:10.1126/science.131.3409.1292. PMID 14399717.

- ^ a b c Pocheville, Arnaud (2015). "The Ecological Niche: History and Recent Controversies". In Heams, Thomas; Huneman, Philippe; Lecointre, Guillaume; et al. (eds.). Handbook of Evolutionary Thinking in the Sciences. Dordrecht: Springer. pp. 547–586. ISBN978-94-017-9014-7.

- ^ Gause, Georgii Frantsevich (1934). The Struggle For Existence (1st ed.). Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins. Archived from the original on 2016-11-28. Retrieved 2016-11-24 .

- ^ Darwin, Charles (1859). On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life (1st ed.). London: John Murray. ISBN1-4353-9386-4.

- ^ Grinnell, J. (1904). "The Origin and Distribution of the Chestnut-Backed Chickadee". The Auk. American Ornithologists' Union. 21 (3): 364–382. doi:10.2307/4070199. JSTOR 4070199.

- ^ Gause, G.F. (1932). "Experimental studies on the struggle for existence: 1. Mixed population of two species of yeast" (PDF). Journal of Experimental Biology. 9: 389–402. doi:10.1242/jeb.9.4.389.

- ^ Hutchinson, George Evelyn (1961). "The paradox of the plankton". American Naturalist. 95 (882): 137–145. doi:10.1086/282171. S2CID 86353285.

- ^ MacArthur, R.H. (1958). "Population ecology of some warblers of northeastern coniferous forests". Ecology. 39 (4): 599–619. doi:10.2307/1931600. JSTOR 1931600. S2CID 45585254.

- ^ Lack, D.L. (1945). "The Galapagos finches (Geospizinae); a study in variation". Occasional Papers of the California Academy of Sciences. 21: 36–49.

- ^ De León, LF; Podos, J; Gardezi, T; Herrel, A; Hendry, AP (Jun 2014). "Darwin's finches and their diet niches: the sympatric coexistence of imperfect generalists". J Evol Biol. 27 (6): 1093–104. doi:10.1111/jeb.12383. PMID 24750315.

- ^ Rastetter, E.B.; Ågren, G.I. (2002). "Changes in individual allometry can lead to coexistence without niche separation". Ecosystems. 5: 789–801. doi:10.1007/s10021-002-0188-3. S2CID 30089349.

- ^ Moll, J.D.; Brown, J.S. (2008). "Competition and Coexistence with Multiple Life-History Stages". American Naturalist. 171 (6): 839–843. doi:10.1086/587517. PMID 18462131. S2CID 26151311.

- ^ Clayton, D.H.; Bush, S.E. (2006). "The role of body size in host specificity: Reciprocal transfer experiments with feather lice". Evolution. 60 (10): 2158–2167. doi:10.1111/j.0014-3820.2006.tb01853.x. PMID 17133872. S2CID 221734637.

- ^ Harbison, C.W. (2008). "Comparative transmission dynamics of competing parasite species". Ecology. 89 (11): 3186–3194. doi:10.1890/07-1745.1. PMID 31766819.

- ^ Hutchinson, G. E. (1959). "Homage to Santa Rosalia or Why Are There So Many Kinds of Animals?". The American Naturalist. 93 (870): 145–159. doi:10.1086/282070. ISSN 0003-0147. JSTOR 2458768. S2CID 26401739.

- ^ Leibold, MATHEW A. (1998-01-01). "Similarity and local co-existence of species in regional biotas". Evolutionary Ecology. 12 (1): 95–110. doi:10.1023/A:1006511124428. ISSN 1573-8477. S2CID 6678357.

- ^ Weiher, Evan; Keddy, Paul A. (1995). "The Assembly of Experimental Wetland Plant Communities". Oikos. 73 (3): 323–335. doi:10.2307/3545956. ISSN 0030-1299. JSTOR 3545956.

- ^ Derrickson, E. M.; Ricklefs, R. E. (1988). "Taxon-Dependent Diversification of Life-History Traits and the Perception of Phylogenetic Constraints". Functional Ecology. 2 (3): 417–423. doi:10.2307/2389415. ISSN 0269-8463. JSTOR 2389415.

- ^ Cahill, James F.; Kembel, Steven W.; Lamb, Eric G.; Keddy, Paul A. (2008-03-12). "Does phylogenetic relatedness influence the strength of competition among vascular plants?". Perspectives in Plant Ecology, Evolution and Systematics. 10 (1): 41–50. doi:10.1016/j.ppees.2007.10.001. ISSN 1433-8319.

- ^ Violle, Cyrille; Nemergut, Diana R.; Pu, Zhichao; Jiang, Lin (2011). "Phylogenetic limiting similarity and competitive exclusion". Ecology Letters. 14 (8): 782–787. doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2011.01644.x. ISSN 1461-0248. PMID 21672121.

- ^ Tarjuelo, R.; Morales, M. B.; Arroyo, B.; Mañosa, S.; Bota, G.; Casas, F.; Traba, J. (2017). "Intraspecific and interspecific competition induces density‐dependent habitat niche shifts in an endangered steppe bird". Ecology and Evolution. 7 (22): 9720–9730. doi:10.1002/ece3.3444. PMC5696386. PMID 29188003.

- ^ Webb, Campbell O.; Ackerly, David D.; McPeek, Mark A.; Donoghue, Michael J. (2002). "Phylogenies and Community Ecology". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 33 (1): 475–505. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.33.010802.150448.

- ^ Burns, Jean H.; Strauss, Sharon Y. (2011-03-29). "More closely related species are more ecologically similar in an experimental test". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 108 (13): 5302–5307. Bibcode:2011PNAS..108.5302B. doi:10.1073/pnas.1013003108. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC3069184. PMID 21402914.

- ^ Cavender-Bares, J.; Ackerly, D. D.; Baum, D. A.; Bazzaz, F. A. (June 2004). "Phylogenetic overdispersion in Floridian oak communities". The American Naturalist. 163 (6): 823–843. doi:10.1086/386375. ISSN 1537-5323. PMID 15266381. S2CID 2959918.

- ^ Kraft, Nathan J. B.; Cornwell, William K.; Webb, Campbell O.; Ackerly, David D. (August 2007). "Trait evolution, community assembly, and the phylogenetic structure of ecological communities". The American Naturalist. 170 (2): 271–283. doi:10.1086/519400. ISSN 1537-5323. PMID 17874377. S2CID 7222026.

- ^ a b Fog, Agner (2017). Warlike and Peaceful Societies: The Interaction of Genes and Culture. Open Book Publishers. doi:10.11647/OBP.0128. ISBN978-1-78374-403-9.

What Is the Definition of Competitive Exclusion Principle in Biology

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Competitive_exclusion_principle